The 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional), better known as "Merrill's Marauders," had become so weakened in seizing the airfield at Myitkyina that Lt. Gen. Joseph Stilwell had to call on the 209th and 236th Engineer Combat battalions to take the nearby town.

Wingate’s exploits so impressed Winston

Churchill that the British Prime Minister summoned this “man of genius and

audacity” to the Quebec Conference in August 1943. At Quebec, the Allies

finally agreed to launch an offensive into Burma in early 1944. While the

Chinese Y Force advanced from Yunnan into eastern Burma and the British IV

Corps drove east into Burma from Manipur State, Stilwell’s Chinese-American

force would attack southeast from the Shingbwiyang area toward Myitkyina.

Capture of that key North Burma city and its airfield would remove the threat

of enemy fighter planes to transports flying the Hump and also enable the

Allies to connect the advancing Ledo Road into the transportation network of

North Burma. A new Southeast Asia Command (SEAC) under British Admiral Lord

Louis Mountbatten would provide overall control to the offensive. After

listening to Wingate’s impassioned arguments on the benefits of Chindit-style

long-range penetration groups, the Allied leaders also agreed to expand the

number of such groups to support the advance, and the Americans agreed to

supply their own long-range penetration force.

The American force which emerged, the

5307th Composite Unit (Provisional) known as GALAHAD, proved a far cry from the

elite unit which the Army’s leaders had envisioned. In the South and Southwest

Pacific, the Caribbean, and the United States, the call for jungle-tested

volunteers for a hazardous mission produced a collection of adventurers,

small-town Midwesterners, southern farm boys, a few Native and

Japanese-Americans, and a number of disciplinary cases that commanders were

only too happy to unload. As the volunteers assembled in San Francisco, one

officer remarked, “We’ve got the misfits of half the divisions in the country.”

After arriving in Bombay, India, on 31 October, GALAHAD trained in long-range

penetration tactics under Wingate’s supervision and soon earned a reputation as

an unruly outfit. A British officer, who had been invited to GALAHAD’S camp for

a quiet Christmas evening, noted men wildly firing their guns into the air in

celebration and remarked, “I can’t help wondering what it’s like when you are

not having a quiet occasion.” Although GALAHAD presented some disciplinary

problems, Stilwell and his staff were overjoyed to obtain some American combat

troops, and Stilwell managed to wrest control of the unit from the angry

Wingate. To command GALAHAD, he selected one of his intimates, Brig. Gen. Frank

D. Merrill, leading correspondents to dub the unit “Merrill’s Marauders.”

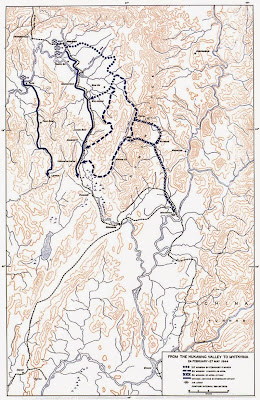

By the time GALAHAD reached the front in

February 1944, Stilwell had already started his Chinese divisions into Burma.

He had received word of Chiang’s decision to cancel the offensive into eastern

Burma but was determined to continue regardless of Y Force’s plans. Taking

command in the field on 21 December, he sent his Chinese troops southeast into

the Hukawng Valley of northern Burma. The Chinese received a major boost in

morale when a battalion of their 114th Regiment, with artillery support, drove

the Japanese from a series of pillboxes and relieved a pocket of trapped troops

at Yupbang Ga. Although a small victory, it made the Chinese believe that they

could meet the enemy on equal terms. Despite this new confidence, the advance

proceeded slowly, due to heavy seasonal rains and Chiang’s tendency to bypass

Stilwell and direct his officers not to risk their men unduly. Using wide

envelopments to outflank the Japanese defenses, the Chinese pushed to the line

of the Tanai Hka, about sixty miles into the Hukawng Valley, by late February.

With GALAHAD’S arrival on the scene,

Stilwell continued to press the advance. He ordered his two Chinese divisions

to keep pressure on the Japanese front and sent the Marauders on a wide march

around the Japanese right to cut the enemy’s communications. Once again, the

Chinese advanced at a snail’s pace, heeding Chiang’s orders to conserve

strength. Noting the glacial pace of the Chinese, Lt. Gen. Shinichi Tanaka,

commander of the Japanese 18th Division, decided to leave a force to block the

Chinese and destroy the threat to his rear.

The Marauders were living up to their image

in Stilwell’s headquarters as a modern-day version of Stonewall Jackson’s foot

cavalry. To reach the Japanese lines of communications, they needed to make

their way through jungle-choked terrain cut by frequent streams and crossed by

only a few trails. When the advance began on 24 February, the intelligence and

reconnaissance platoons of GALAHAD’S three battalions took the lead, carefully

probing ahead in single file on the narrow footpaths through the dense foliage,

examining footprints, stopping frequently to watch and listen, cautiously

approaching each bend in the trail. Occasionally, they clashed with Japanese

patrols. Near the village of Lanem Ga, a burst of fire from a Japanese machine

gun claimed the life of Pvt. Robert W. Landis, the lead scout of the 2d

Battalion’s intelligence and reconnaissance platoon and the first Marauder to

die in combat. On 3 March the Marauders reached the Japanese line of retreat

and established a pair of roadblocks, the 3d Battalion at the little Kachin

village of Walawbum, the 2d farther northwest near Kumnyan Ga, and the 1st in

reserve. Digging in, they waited for the enemy’s response.

The Japanese did not take long to act. At

Walawbum, the 56th Regiment struck the positions of the Orange Combat Team of

the 3d Battalion on 4 March and 6 March. The emphasis on marksmanship in

GALAHAD’S training now paid dividends as the Americans, aided by heavy mortars

firing from their rear and by two heavy machine guns, littered the fields with

Japanese dead. On the day of the 6th, the Japanese launched a banzai attack,

but the frenzied enthusiasm of the assault again proved no match for American

firepower. To the north the 2d Battalion came under severe pressure, repulsing

six attacks in one day, before Merrill withdrew them. In all, the Marauders

killed about 800 enemy soldiers at a cost of 200 of their own men. As pleased

as they were with such a performance, Stilwell and Merrill were anxious to keep

down GALAHAD’S losses, particularly given its status as the only available

American combat unit. They relieved the Marauders with a Chinese regiment on 7

March. By that time, Tanaka had decided to withdraw south along a hastily built

bypass of the American roadblocks to a strong position on the Jambu Bum, a

range of low hills at the southern end of the Hukawng Valley.

In his plan for the campaign, Stilwell had

hoped to reach the Jambu Bum before monsoon rains forced suspension of active operations.

His divisions were practically the only Allied force making progress in the

campaign. Not only had Chiang postponed Y Force’s advance, but the British, far

from moving into Burma, were trying to hold against a major Japanese offensive

into India. This Japanese advance, which began on 8 March, threatened both the

British Army in Assam and Stilwell’s supply line to India. For the moment

Stilwell could still proceed, but he would have to keep a close watch on

developments to the southwest. He accordingly laid plans for the Chinese to

continue their advance on the 18th Division’s front, while GALAHAD would split

into two parts, again envelop the Japanese right flank, and cut Japanese

communications in two different places.

In this flanking movement, GALAHAD had to

march through some of the most difficult terrain of the campaign. The Marauders

needed to climb out of the Hukawng Valley onto the hills to the east and then

move south through territory in which only the extremely steep, narrow valley

of the Tanai offered an avenue of approach. Fortunately, the Marauders in their

march unexpectedly encountered the Kachin guerrillas, who served as guides,

screened the advance, and even provided elephants as cargo bearers. On the

right the 1st Battalion hacked a path through twenty miles of bamboo forests

and streams, crossing one river fifty-six times. Early on the morning of 28

March the battalion surprised an enemy camp at Shaduzup and established a

roadblock. To the south Col. Charles N. Hunter, Merrill’s second in command,

led the 2d and 3d Battalions up the Tanai and through ridge lines to take up a

position near Inkawngatawng. They had hardly arrived when they received orders

to retrace their steps and take up blocking positions. A captured enemy sketch told

Stilwell that a strong Japanese force was advancing on the Allied left to

outflank the attackers. To head off the Japanese, the 3d Battalion occupied

Janpan and the 2d Battalion took up positions at Nhpum Ga.

At Nhpum Ga the 2d Battalion withstood eleven

days of shelling and heavy attacks from three Japanese battalions which

surrounded the position. The 2d’s perimeter, 400 by 250 yards on top of a 2,800

foot saddle of high ground, dominated the surrounding terrain, but it offered

few amenities to battalion members. The Japanese captured the only water hole,

necessitating airdrops of water into the position. The stench from rotting mule

carcasses and unburied excrement, according to one soldier, “would have been

utterly unbearable if there had been any alternative to bearing it.” Yet,

somehow, the 2d managed to hold. Its Japanese-American soldiers frequently

crept into no-man’s-land at night, eavesdropping on Japanese conversations to

discover the enemy’s intentions. Meanwhile, the rest of GALAHAD rushed to the

rescue. The 1st Battalion, leaving its position at Shaduzup to the Chinese,

hastened to the aid of the 2d, and Merrill, though evacuated with a heart

attack, arranged the drop of a pair of pack howitzers to the relief forces.

Aided by this artillery fire, the 1st and 3d Battalions finally broke through

and relieved the 2d on 9 April.