The Hump Honey out of Cheng-tu China.

The Lady Boomerang out of Paindota India, July 1944.

The decision to mount the invasion of Japan from island

bases without benefit of a lodgment on the east China coast meant that the war

would end, as it had been waged throughout, with no real connection between the

Pacific theaters and China-Burma-India. In the latter theater problems of

strategy and command had been even more difficult of solution than in the

Pacific, being rooted in the divergent interests of the three Allied nations

and made bitter by the personal animosities of some leaders. China-Burma-India,

lying at the extreme end of the supply line from America, was accorded a very

low priority, and geographical factors within the theater made it difficult to

use the bulk of the resources in combat: most of the tonnage available was

spent merely in getting munitions to the various fronts. There were few U.S.

ground forces in CBI, most of the troops being air or service forces whose

mission was to see that a line of communication was preserved whereby China

could be kept in the war.

The Tenth Air Force, having earlier protected the southern

end of the Assam-Kunming air route that was long the only connection between

China and U.S. supply bases in India, was committed in mid- 1944 to a campaign

in northern Burma whose dual objective was to open a trace for the Led0 Road

into China and to secure bases for a more economical air route over the Hump.

By that time Allied air forces, combined in the Eastern Air Command, had

control of the skies over Burma; they helped isolate the strategic town of

Myitkyina, supplied by airlift the ground forces conducting the siege, and

rendered close support in the protracted battle that dragged on from May to

August. After the fall of Myitkyina, the Tenth Air Force participated in the

drive southward to Rangoon, a campaign that would seem to have borne little

relation to the primary American mission. In both air support and air supply

the Tenth showed skill and flexibility, but these operations absorbed resources

that might have accomplished more significant results in China. After the Burma

campaign EAC was dissolved in belated recognition of differing interests of the

Americans and British, and at the end of the war the Tenth was moving into

China to unite with the Fourteenth Air Force.

That force, ably commanded by Maj. Gen. Claire E. Chennault,

had developed tactics so effective that its planes had been able to support

Chinese ground forces and strike at shipping through advanced bases in east

China while giving protection to the northern end of the Hump route. Chennault

believed that if his force and the airlift upon which it depended could be

built up, air power could play a decisive role in ejecting the Japanese from China.

The promised build-up came too slowly. In the spring of 1944 the Japanese

started a series of drives which gave them a land line of communication from

north China to French Indo-China, a real need in view of the insecurity of

their sea routes, and the drives in time isolated, then overran, the eastern

airfields which had been the key to much of Chennault’s success. In the

emergency, a larger share of Hump tonnage was allocated to the Fourteenth and

totals delivered at Kunming by ATC grew each month, dwarfing the tiny trickle

of supplies that came over the Ledo Road. Chennault received too some

additional combat units, but the time lag between allocation of resources and

availability at the front was fatal. Different views of strategy and personal

disagreements between Chennault and Chiang Kai-shek on the one side and Lt.

Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell, the theater commander, on the other resulted in the

relief of Stilwell and the division of CBI into two theaters, India- Burma and

China, with Lt. Gen. Albert C. Wedemeyer commanding the latter. Heroic efforts

by air, including mass movements of Chinese ground forces by plane, prevented

the Japanese from overrunning all China. In the last months of the war the

combined Fourteenth and Tenth Air Forces were preparing for a final offensive,

but the surrender came before this could be developed.

The command system in CBI and logistical problems as well

were made more complicated by the deployment in that theater of XX Bomber

Command, an organization equipped with B-29 bombers and dedicated to a doctrine

of strategic bombardment. The plane, an untried weapon rated as a very heavy

bomber, had been developed during the expansion of the Air Corps that began in

1939, and its combat readiness in the spring of I 944 had been made possible

only by the Air Staff’s willingness to gamble on short-cuts in testing and

procurement. The bomber command, which resembled in many respects an air force

rather than a command, had also been put together in a hurry, and the mission

in CBI was conceived both as a shakedown for plane and organization and as an

attack on Japanese industry. Early plans had contemplated using the B-29

against Germany, but by the summer of 1943 thoughts had turned to its

employment against Japan. The prospect that some time would elapse before

appropriate bases in the Pacific could be seized plus the desire to bolster the

flagging Chinese resistance to Japan, a need in which President Roosevelt had

an active interest, led to a decision to base the first B-29 units in CBI. The

plan looked forward also to VHB operations from the Marianas, where U.S.

Marines landed on the same day that XX Bomber Command flew its first mission

against Japan.

To insure flexible employment of a plane whose range might

carry it beyond existing theater limits, the JCS established the Twentieth Air

Force under their own control with Arnold as “executive agent.” Theater

commanders in whose areas B-29 units operated would be charged with logistical

and administrative responsibilities, but operational control would remain in

the Washington headquarters. This system of divided responsibilities found its

severest test in CBI where the command system was already confused and where

the dependence on air transport led to fierce competition for all supplies laid

down in China.

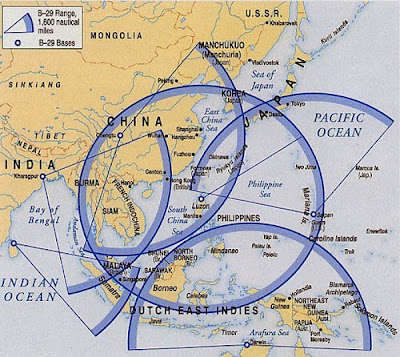

Operational plans (MATTERHORN) for XX Bomber Command

involved the use of permanent bases at Kharagpur near Calcutta and of staging

fields near Chengtu in China, within B-29 radius of Kyushu and Manchuria but

not of Honshu. Supplies for the missions were to be carried forward to Chengtu

by the B-29’s and by transport planes assigned to the command. Delays in the

overseas movement of the B-29’s and in airfield construction held up combat

operations, the first regular mission being sent against Yawata on 15 June.

The earliest target directives gave precedence to the steel

industry, to be attacked through bombing coke ovens. This target system was

basic to the whole Japanese war effort and it had the tactical advantage of

lying within range of the Chengtu bases. Little damage was done in Japan

proper, but a few missions against Manchurian objectives were more effective

than was then realized, From the beginning, operations were strictly limited by

the difficulty of hauling supplies, especially fuel and bombs, to the forward

bases. It was impossible for XX Bomber Command to support a sustained

bombardment program by its own transport efforts, and the Japanese offensive in

east China which began just before the B-29 missions prohibited any levy on

normal theater resources, When the B-29’S were assigned a secondary mission of

indirect support of Pacific operations, logistical aid was furnished in the

form of additional transport planes which were first operated by the command,

then turned over to ATC in return for a flat guarantee of tonnage hauled to

China.

Because support of Pacific operations was designed to

prevent the enemy from reinforcing his air garrison during the invasion of the

Philippines, XX Bomber Command shifted its attention to aircraft factories,

repair shops, and staging bases in Formosa, and factories in Kyushu and

Manchuria. This shift from steel, considered a long-term objective, to aircraft

installations reflected recent decisions to speed up the war against Japan.

Attacks against the newly designated targets, begun in October, were moderately

successful, but a new Japanese drive lent urgency to the need for additional

logistical support for ground and tactical air forces in China; consequently,

at the request of General Wedemeyer, the command abandoned its Chengtu bases in

mid-January 1945.

Earlier, the B-29’s had run a number of training missions in

southeast Asia and one strike, from a staging field that had been built in

Ceylon, against the great oil refinery at Palembang in Sumatra; now the giant

bombers continued with attacks against Burma, Thailand, Indo-China, and Malaya.

Strategic targets, as defined by the Twentieth Air Force, were lacking, and

though some important damage was done to the docks at Singapore, operations had

taken on an air of anticlimax long before the last mission was staged on 30

March. At that time the command was in the midst of the last and most sweeping

of a series of reorganizations: the 58th Bombardment Wing (VH), its only combat

unit, was sent to Tinian where it became part of XXI Bomber Command, while the

headquarters organization went to Okinawa to be absorbed by the Eighth Air

Force.

Measured by its effects on the enemy’s ability to wage war,

the MATTERHORN venture was not a success. For want of a better base area it had

been committed to a theater where it faced a fantastically difficult supply

problem. Something of the difficulty had been realized in advance, but the

AAF’s fondness for the concept of a self-sufficient air task force had perhaps

lent more optimism to the plan than it deserved. Certainly the desire to

improve Chinese morale was a powerful argument, and here there may have been

some success, though it would be difficult to prove. Powerful also was the

desire of AAF Headquarters to use the B-29 for its intended purpose, very

long-range attacks against the Japanese home islands, and in justice to that

view it must be noted that the planners from the beginning expected to move the

force to island bases when they were available, just as was done. As an

experiment with a new and complex weapon, MATTERHORN served its purpose well:

the plane was proved, not without many a trouble, under severest field

conditions; tactics were modified and the organization of tactical units

streamlined. The lessons learned were of great value to XXI Bomber Command, but

the necessary shakedown might have been accomplished at less expense elsewhere,

perhaps in the southwest Pacific. At any rate, the editors find no difficulty

in agreeing with USSBS that logistical support afforded to XX Bomber Command in

China would have produced more immediate results if allocated to the Fourteenth

Air Force, though it seems dubious that the alternate policy would have made

for an earlier victory over Japan.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.